From Jacobin

In May 1963, in a Kennedy family living room on Central Park South, Lorraine Hansberry tried to defend civil rights activists’ safety. The Raisin in the Sun playwright had come along with actor Harry Belafonte, author James Baldwin, and other luminaries at the invitation of Robert F. Kennedy and Baldwin. She listened as activist Jerome Smith tried to impress upon the attorney general the level of violence protesters were facing in the South. Smith had come straight from the Freedom Rides for medical treatment on his jaw and head, having been beaten in Birmingham.

The young unknown activist spoke first among the prestigious attendees. He chided Kennedy for not doing enough to protect protesters. On television and in newspapers around the world, it was clear that African American protesters were routinely punched, kicked, spat upon, clubbed, hosed, and had police dogs sicced on them. For what? Wanting to vote? Equal protection? Just being there, he said, made him sick at the administration’s inaction.

When Kennedy turned away from Smith — as if to say, “I’ll talk to all of you, who are civilized. But who is he?” — Hansberry “unleashed,” Imani Perry writes in her recent biography. There were many accomplished individuals in the room, Hansberry said, but Smith’s was the “voice of twenty-two million people.” Kennedy should not only listen; he should give his “moral commitment” to protect those like Smith.

The meeting ended abruptly. Hansberry invited Smith to speak at a fundraiser a week later in Westchester, which raised $5,000. Part of that amount purchased a Ford station wagon that turned up in the news a year later: empty, burned, the three civil rights workers missing. A month after the car was found, the Freedom Riders were discovered dead in a ditch. What if Bobby Kennedy had listened to Smith?

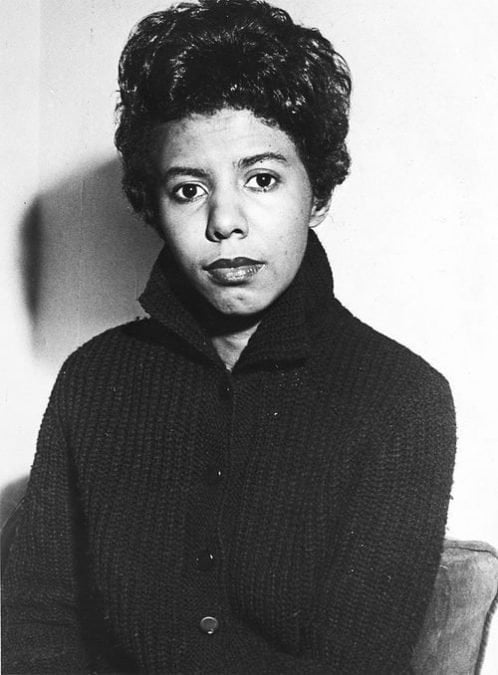

The oft-told vignette is given new urgency in Perry’s Looking for Lorraine, a powerful retelling of Hansberry’s short but dazzling life. (Perry also offers her insights in Tracy Heather Strain’s visually beautiful 2017 documentary Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart.)

The first black woman playwright to produce a play on Broadway and the daughter of the first black family to move into white Chicago, Hansberry grew distrustful of the cult of firsts, as well as of celebrity activism and liberal incrementalism. Though she died at thirty-four and only produced two plays during her lifetime, her work and ideas continue to reverberate; since her 1965 death, a Hollywood, Broadway, or other large-scale adaptation of A Raisin in the Sun has come out at least once per decade, along with a stream of posthumous plays and prose.

But like her friend James Baldwin, it is Hansberry’s political pronouncements that resonate most profoundly — scattered but potent arrows that, as Perry writes, gave “public voice to her belief that the Black working class [was] at the center of the struggle for liberation, and that she must be an amplifier, not a figurehead.”

A Brick

Lorraine Hansberry’s father’s successes, and failures, rushed into her consciousness one afternoon. They piggybacked on a brick that flew through her window, almost crushing her.

Carl Hansberry migrated from Mississippi, where he had studied at Alcorn State. Her mother, Nannie, migrated from Tennessee. The youngest of four, Lorraine came into the world on May 19, 1930 (sharing a birthday with Malcolm X). Her mother gave birth in “Provident, the first Black owned and operated hospital in the nation.”

Carl was in real estate. As black transplants crowded into Chicago, Hansberry (“the Kitchenette King”) cut larger apartments into smaller units. “The kitchenettes allowed Carl . . . to provide housing for Black residents who, due to discrimination, were squished into far too small a terrain.” With the considerable money he made from real estate, Carl gave to organizations that sought to end racial discrimination. He became secretary of the local NAACP chapter, donating $10,000 to endow the Hansberry Foundation. Lorraine looked up to him — by some accounts, worshipped him.

As a girl, Lorraine spent time alone, thinking, observing. “The honesty of their living is there in the shabbiness,” she wrote of the poor black families surrounding her, “scrubbed porches that sag and look their danger. Dirty gray wood steps. And always a line of white and pink clothes . . . waving in the dirty wind of the city. . . . Our south side is a place apart . . . each piece of our living is a protest.”

In spring 1937, Carl bought a house in the South Side neighborhood of Woodlawn, expecting a legal battle. The house, at 6140 South Rhodes Avenue, was just inside the “white section” enforced by restrictive covenants. One day, the family bodyguard saw a crowd outside. He led Lorraine and her sister, Mamie, inside, “and that’s when they threw this huge piece of mortar,” Mamie recalls in Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart. “That mortar lodged in the wall. And just missed [Lorraine],” who was seven.

As Perry notes on-screen, “It’s in that moment that she recognizes that notwithstanding her family’s prosperity, she was still going to be subjected to racial violence like every other Black American.” Hansberry recalled “my desperate and courageous mother patrolling our house all night with a loaded German Luger, doggedly guarding her four children.”

These battles were not unique. “There were literally hundreds of cases across the Midwest of white mob violence in response to individual efforts to integrate,” Perry writes. “The consequences were destroyed property, lost homes, trauma, and sometimes death.” While in the South racial apartheid meant segregated public transportation and lynching, up north, “real estate was the border of racial status.”

Around when the brick landed in the drywall, Nannie and Carl took the children on a trip to her mother’s Tennessee. While driving, they passed the hills of Kentucky, where Nannie “directed her children, from the car, to look at the hills.” Nannie recalled

that her father, their grandfather, had escaped to [those hills] when he was a boy. A runaway slave as a child, he was protected by his own mother. She kept him alive by wandering into the forested hills in the middle of the night, leaving food and other provisions. Lorraine found the hills beautiful.

“I Must Perhaps Go to Jail”

Soon after moving, a ruling forced the Hansberrys out of their new house. Carl appealed to the Supreme Court, yielding a partial victory three years later. While the court upheld the restrictive covenant, it deemed the contracts poorly written; the Hansberrys could stay at 6140 South Rhodes Avenue. The court also opened up five hundred new properties to black residents.

Through the NAACP and other civil rights groups, Carl and Nannie attacked segregation in travel and in the military. But they began to feel that little had been gained. After years of striving, they recognized with bitterness that Chicago was still segregated. They decided to move to Mexico City. Carl felt free for the first time in his life.

Lorraine stayed in Chicago to complete her schooling, where, despite segregation, an efflorescence of cultural and artistic expression had taken place in Lorraine’s youth, a Black Renaissance. Black writers’ collectives grew out of the Communist Party. “Perhaps the most important project in the 1930s for Black Chicagoans,” writes Perry, “was the Negro in Illinois project of the [New Deal’s Works Progress Administration],”

which enlisted dozens of workers to study the world of Black Chicago under the directorship of Black sociologists . . . Among the writers who worked on the Negro in Illinois were future literary luminaries Gwendolyn Brooks, Richard Wright, and Margaret Walker.

Two months before her sixteenth birthday, Lorraine received a devastating telegram: her father had died of a cerebral hemorrhage. “In reflection years later,” writes Perry, “Lorraine would describe her father as a ‘real American type American,’ who believed in struggling for equality ‘the respectable way.’ And yet it was clear . . . that such efforts were rarely rewarded in kind.” Lorraine would later write that “the cost in emotional turmoil, time and money” of his battles against segregation “led to my father’s early death.”

After two years at the University of Wisconsin, Hansberry arrived in New York, seeking “an education of another kind.” She moved uptown to take a job at a new magazine in Harlem called Freedom, launched by left-wing actor, singer, and activist Paul Robeson. At Freedom, she amassed a number of bylines, reviewing Richard Wright’s The Outsider (“exalts brutality”), Howard Fast’s Spartacus (should have been told through the eyes of the enslaved), and the Japanese film Hiroshima (defending it as both propaganda and art). Described by her editor in chief as “the girl who could do everything,” she joined the Communist Party and Labor Youth League, and wore many hats, thinking and writing on a much broader, more global canvas than ever before.

Hansberry wrote about independence movements in Africa, praised her uncle Leo’s former student, Kwame Nkrumah, who fought for Ghanaian independence, and began to see the fight against Jim Crow in the United States as part of an international struggle of black and brown people. She took up poetry, publishing in Masses & Men on topics such as life in poor Chicago and the execution of Willie McGee, a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman.

In exchanges from Harlem with friends from college, Hansberry now fully embraced her leftism, writing, “I am sick of poverty, lynching, stupid wars and the universal maltreatment of my people and obsessed with a rather desperate desire for a new world for me and my brothers. So dear friend, I must perhaps go to jail. Please at the next painting session you have to . . . remember this ‘Communist!’”

Condemned by the State

Around the same time, Hansberry began studying at the Jefferson School of Social Science, a Communist Party–affiliated center for adult education in Harlem, where she befriended one of its luminary instructors, W. E. B. Du Bois. The famed radical “recognized Lorraine’s gifts, and . . . she became his favorite student . . . gifted enough to teach others as well as study under his tutelage.”

The admiration was mutual. Hansberry praised Du Bois’s mind and manner in her diary. “Tenderly noting his idiosyncrasies alongside the enormity of his influence,” writes Perry, “she distilled Du Bois [as] freedom’s passion personified. . . . Her own admiration of beauty and elegance, her own aspirations toward the life of the mind, sat there in front of her.” Jotting down his bon mots — “Somehow you have got to know more than what you experience individually” — she conceived a moral and political action plan, a politics based on understanding others’ needs with one’s own.

However influential Du Bois was on the Left, McCarthyism had rendered him persona non grata. He and Robeson “were prime targets within an intellectual and political community of Black socialists and communists who were under surveillance,” writes Perry. “Being a communist wasn’t strange back then.” But it did make “you vulnerable to steady attack from the powerful.” Du Bois had circulated a petition against nuclear weapons, “and in response he was arrested and indicted for being an agent of the Soviet Union.”

Efforts to discredit black activists and leftists as agents of the Soviet Union, particularly during the Korean War, was a standard ploy. Du Bois’s peace and anti-nuclear weapons organization, the Peace Information Center, was forced to register as a foreign agent. When Du Bois and his comrades refused, they were arrested.

“As a result of the trial,” writes Perry,

he became a pariah in many circles. At the time when Lorraine sat before him as a student, he was so stigmatized that he found himself struggling to buy groceries. And in 1952, his passport was revoked. The State Department claimed they took it because they could not authorize him to attend a peace conference in Canada, but it had the effect of limiting his connections and political influence and potentially his moving abroad.

The case was dismissed when his defense attorney announced that Albert Einstein would appear as a character witness. And while other luminaries, like Langston Hughes, stood by him, Du Bois was embittered by those who wouldn’t, like the NAACP, which Du Bois had cofounded in 1909, but which refused to issue even a mild statement of support.

Meanwhile, Robeson’s passport had already been revoked, blocking his work as a global entertainer and activist. As a result of the ban, Lorraine agreed to go as his proxy to the Inter-American Peace Conference in Montevideo, Uruguay, in March 1952, which was being held underground to avoid repression. At the 280-delegate conference, Hansberry was one of five US delegates who witnessed the organizers’ necessary subterfuge, which “consisted of delegates pretending they were having parties by playing loud music and dancing outdoors. . . . Whenever they retreated indoors,

they delivered conference papers. On Lorraine’s first full day of the conference, she attended a women’s meeting . . . and listened to an address by a former woman deputy of the Uruguayan Parliament. After the address there was some communication in Spanish that Lorraine didn’t understand. . . . A woman approached her and said, in English, that Lorraine had been one of the honored women who should sit on the presidium and speak. Stunned, Lorraine stepped up to deliver her report.

Soon interrupted by police, Hansberry watched the gathering camouflage itself as a prissy ladies’ tea. When the police left, Hansberry continued. The Brazilian delegate honored her with red carnations; she was moved, thinking “of the women who had been jailed and terrorized in the US for their activism . . . of her people suffering, and she was honored to be selected, the sole Black American woman at the conference, to represent them all.”

That summer, after Lorraine continued to teach at the Jefferson School, the State Department knocked on the door at her mother’s house and confiscated her passport. She was twenty-two.

The Communist Line?

Two years after Hansberry moved to New York, a comrade from the Labor Youth League, Robert Nemiroff, began courting her. When the relationship threatened to get serious, she wrote him a firm reminder of her priorities, admitting that “I do love you, you wide-eyed immature unsophisticated revolutionary,” adding,

- I am a writer. I am going to write.

- I am going to become a writer.

- Any real contribution I make to the movement can only be the result of a disciplined life. I am going to institute discipline in my life.

- I can paint. I am going to paint.

THE END.

They married on the same sweltering weekend in June 1953 that Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed for espionage. The specter haunted their wedding. Hansberry recalled a ceremony overshadowed by “the desire . . . to thrust one’s arms into the air . . . screaming at one’s countrymen to come . . . down from the houses, to get up from the television sets, from the dinner tables.” The bride, she wrote, “sits a moment in the corner, alone . . . she thinks . . . And what shall I say to my children?”

This was a rhetorical question. Hansberry would never have children. But after reading Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, “her mind afire . . . with ideas from France,” she also doubted marriage. The book would shape her and Nemiroff’s anything-but-conventional partnership. Like his new wife, Nemiroff wanted to write, but he repeatedly committed himself to supporting her work.

After Lorraine left Freedom, both took odd jobs. Nemiroff then wrote a pop love song off a Calypso standard, it became a hit, and the windfall allowed Hansberry to write full time. The pressure could sometimes overwhelm her. Sighted Eyes reenacts a moment when she tosses the manuscript of A Raisin in the Sun in the air, and Nemiroff quietly collects the pages from the floor, sets them aside. A few days later, he places them before her; she nods and gets back to work.

Eventually, the couple invited producer Phil Rose to spaghetti, and Hansberry read her play aloud, after serving banana cream pie. “Here was a family living in the Chicago South Side ghetto,” writes Perry of the play’s story. “Armed with a $10,000 life insurance check after the death of the father, they hope to move out of their tiny kitchenette apartment and into a house in a segregated white neighborhood. The adult son, Walter Lee, dreams of becoming a businessman. His sister, Beneatha, aspires to become a doctor. The matriarch, Lena, and her daughter-in-law are most of all hoping for a home of their own.”

Rose telephoned Hansberry in the morning. “I want to produce your play,” he said.

Sidney Poitier was cast as Walter Lee Younger, but told Strain that investors were scared no audience would come. Hoping to prove that “greed [might] triumph over bigotry,” they put the play up in New Haven, Philadelphia, and Chicago. A thousand black actors lined up to audition. The early buzz caught the eye and ear of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

When tryouts started, the agency had already been tailing Hansberry for years. But before looking over her literary work, they reviewed her style, noting in one memo her “Italian cut” hairstyle. The media did the same, also mistaking Hansberry’s looks with her politics. “Her physical beauty and grace added to their confusion about who she actually was, politically speaking,” writes Perry. Vogue depicted Hansberry “as a woman still dressed in the ‘collegiate style.’” After the local New Haven branch missed its run there, Hoover ordered a New York–based special agent “to conduct a necessary investigation to establish whether the play . . . is controlled or influenced by the Communist Party [or] in any way follows the Communist line.”

Their definition was capacious: any figure or material critical of US Cold War policy could be deemed beyond the pale. After the peace conference in Uruguay, the agency had placed Hansberry on its Security Index, a list of supposedly dangerous and presumably disloyal Americans who were to be rounded up in camps in the event of war, or some other emergency.

For the country’s top law enforcement agency, reviews and clippings of the play weren’t enough to gauge whether it toed the Communist line. So a Philadelphia special agent was sent to the Walnut Street Theater. “The play contains no comments of any nature about Communism as such,” the agent deadpanned. And he went on, across four pages, to describe the play’s views on “negro aspirations, the problems inherent in their efforts to advance themselves.”

In the same February 5, 1959, memo, the agent explained that he opted not to follow through with an interview of Hansberry since “the subject and her play have received considerable notoriety in the NY press . . . and the Bureau could be placed in an embarrassing position if it became known . . . that the Bureau” was investigating writers like Hansberry.

A Keynote, Erased

On March 1, 1959, Hansberry was invited to deliver the keynote at the First Congress of Negro Writers at New York’s Hudson Hotel. Almost certainly unbeknownst to her, the CIA had set up the sponsoring organization, the American Society of African Culture, to counter the black radicalism and anti-imperialism of the day, replicating what it had done with cultural movements like the Congress for Cultural Freedom, student groups like the National Students Association, and many others.

Although Langston Hughes was among the attendees, the group arrayed at the Hudson that March day was more conservative in its makeup than the activists Hansberry had met in Montevideo. Her radical talk struck a discordant note.

“One cannot live with sighted eyes and feeling heart and not know the miseries which afflict this world,” she told the crowd. “Let no Negro artist who thinks himself deserving of the title take pen to paper . . . if in doing so the content of that which he presents or performs suggests to the nations of the world that our people do not yet languish under privation and hatred and brutality and political oppression in every state of the forty-eight.”

Speaking of art as a “war against illusions,” Hansberry suggested that “whatever the corruption within our people,” artists must “tear it out and expose it and let us then take the measure of what is left . . . the most painful exigency of cultural and social life will not be exempt from exploration by my mind or pen.” Arguing for self-criticism and radical truth-telling, Hansberry added that any necessary exposure by artists of oversights “of our people will not result in a denigrated image” but will “only heighten and make more real the inescapable image of their greatness and courage.”

That radicals were granted time at the podium of the Hudson Hotel might seem to speak to the honesty of the debate curated by the organizers at AMSAC. But when the published account of the conference appeared in 1960, the only trace of Hansberry was a photograph of her among the attendees. Hers and other radicals’ speeches had been erased from the commemorative booklet. And Hansberry’s speech, “The Negro Writer and His Roots,” remained unpublished for another twenty-one years.

“Propagandistic Writing”

Ten days after her keynote, on March 11, A Raisin in the Sun debuted at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on Broadway. A few black audience members came the first night, the second night more, and by the third night, at least half of those watching were African American.

When the play opened, Poitier was starring in the film Porgy and Bess. Lloyd Richards puzzled out the math: he approached an elderly black audience member and asked her why she was willing to pay $4 for a Poitier play when she could pay 85 cents to see him in a film. She told Richards proudly that she had heard that the play dealt with “something that concerns me.” He never forgot her phrasing.

Opening night ended with a standing ovation and the crowd demanding Hansberry take a bow. She hid in her seat, until Poitier strode into the audience to lead her onstage. The play won the New York Drama Critics Award, completed a long run, was translated into twenty languages, and afforded Hansberry instant celebrity.

Two days after the Broadway premiere, Hollywood producers approached Hansberry, who sought a wider audience for the play, but insisted warily, “No one is going to turn this into a minstrel show . . . And if this blocks a sale, then it just won’t be sold.” In the end, it didn’t block a sale. Columbia optioned it. But battles over her attempts to move the drama outside the Youngers’ South Side apartment and into the streets of Chicago were constant.

One producer wrote that the play’s “race elements” “may lessen the sympathy of the audience, [or] give the effect of propagandistic writing.” Hansberry’s second draft was returned with 106 numbered notes from mogul Samuel Briskin, who tried to excise what he called “jive expressions” and deleted mentions of “Africans,” “revolutionaries,” and more. The strategy for marketing the film in the South was to avoid letting “people know in advance that it’s about negroes,” branding it instead as a prestige film.

Briskin’s Columbia partnered with Glenn E. Miller Productions, its “new arm specializing in film production for military and defense purposes.” Briskin himself had done film propaganda during World War II. Another major studio (Paramount) was found to have a CIA-paid undercover image watchdog on salary, someone who could kill or rewrite scripts to remove critiques of the United States, often excising realistic portrayals of American segregation, poverty, or violence.

But A Raisin in the Sun, which opened ten days after Hansberry’s thirty-first birthday, was a film she could be proud of. Though much that she meant to keep in was left on the cutting room floor, the final result won a special humanitarian honor at the Cannes Film Festival and earned Hansberry a best screenplay nomination from the Screen Actors Guild.

Hearing the Thunder

In 1962, Hansberry moved from Greenwich Village, where she’d lived with Nemiroff, into her own house in Croton, New York. In her journal entries, short stories, anonymous letters, and her social life, Hansberry came out as a lesbian. While she and Nemiroff remained confidantes, friends, and collaborators, the two separated before the play was even finished. Her two acres in the Croton Woods, which she named Chitterling Heights, afforded shelter from the bustle and social obligations of the Village. At Croton, she began work on plays about Haiti’s liberator Toussaint Louverture, white supremacists, and other political dramas, but stomach pains interrupted her work.

One day, James Baldwin called to invite her to a meeting with President Kennedy’s brother, the attorney general. The Kennedys’ initial approach to civil rights had been distant accommodation, hoping to politically manage the protests in a way that wouldn’t reflect poorly on the administration. Until 1963, they remained aloof, effectively allowing violence to besiege protesters in cities across the South while the infrastructure of white supremacy maintained its hold on institutions across the North.

At the meeting, a period of pleasantries preceded Jerome Smith’s criticism of the administration. But one matter obscured in the many retellings of this meeting, Perry notes, was that Smith’s was an anti-war message. The Vietnam war was accelerating. As Harry Belafonte paraphrased, Smith told the attorney general: “In the midst of our oppression, you expect to find us giddily going to fight a war? It’s your war, it’s unjust, unfair, and so dishonorable [that] it should shame you. I wouldn’t pick up a gun to fight for this country. I’d die first.”

This reflex to defend a war, a war in the name of liberals running from the charge of being “soft on communism,” was the impetus for Kennedy’s dismissing Smith, disdainfully turning away, which triggered Hansberry to underline Smith’s words — interrupting the pleasantries to point back at these words. It was only then that the evening “imploded.”

After the group split up, Baldwin took a car to an interview, noticing Hansberry on Central Park South, walking toward Fifth Avenue, “her face twisted, her hands clasped before her belly, eyes darker than any eyes I had ever seen before — walking in an absolutely private place.” He couldn’t call to her; he was already late.

But the winds were blowing in Smith and Hansberry’s direction. Less than a month later, at RFK’s urging, President Kennedy “gave his landmark civil rights address during which he proposed the legislation that would be known as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” In that address, the president “spoke of civil rights as not just a legal issue but also, as Lorraine suggested, a moral one.”

Perry, whose Looking for Lorraine is supple, wise, radical, and intimate, makes another important stipulation. We talk today of the civil rights movement as one movement without debates about tactics, the debates we face today — for instance, about destroyed property and who’s responsible. Perry makes clear that, of course, the same debates took place “back then [when the black protesters on the streets of Birmingham] were considered out of control, pushing too fast and hard.” Moreover, “They raced beyond the authority of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. They had their own local leaders, and they were not uniformly committed to nonviolence.”

This would increasingly be Hansberry’s position: a variety of approaches that scoffed at the notion of going too fast, or of the utility of making only incremental, cautious change, while activists like the three who drove Hansberry’s donated station wagon were being killed. She told white liberals they should be radicals. Lorraine said:

I think then that Negroes must concern themselves with every single means of struggle: legal, illegal, passive, active, violent and non-violent. That they must harass, debate, petition, give money to court struggles, sit in, lie-down, strike, boycott, sing hymns, pray on steps, and shoot from their windows when the racists come cruising through their communities. The acceptance of our present condition is the only form of extremism which discredits us before our children.

As she moved to do more for the movement and theater, Hansberry was struck with pancreatic cancer, ominously depicted by Baldwin’s observation of her leaving the Kennedy meeting. She died on January 12, 1965, at the age of thirty-four.

Malcolm X attended her funeral. He would be murdered five weeks and five days after Hansberry’s death. Martin Luther King sent a message of tribute.

“Her creative ability,” read Dr King’s message, “and her profound grasp of the deep social issues confronting the world today will remain an inspiration to generations yet unborn.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.