From Jacobin

Few legal arenas are more volatile than labor law. With the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) remaining virtually unchanged by Congress since 1959 and the Supreme Court growing increasingly uninterested in interpreting it, the role of creating and changing labor policy governing most private-sector workers in America falls almost entirely upon the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

Inevitably, this results in a wild oscillation of reversed precedent whenever the White House flips between a Democrat or Republican. The new appointees to the NLRB typically make it a priority to overturn as much of the past majority’s decisions as possible, paying special attention to those which recently tilted the doctrinal scales in labor’s or management’s favor. This can create chaotic results in some areas of the law. For example, the question of whether graduate students are covered as employees under the act — and thus possess the right to unionize and collectively bargain — has flipped three times since 2000 and is currently slated to change again.

However, many decisions slip through the cracks. This is especially true for rulings that favor management, as union-sympathetic labor boards have essentially been playing a defensive game of whack-a-mole since the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. Whether it’s because of a lack of time between elections, legislative sabotage by pro-business politicians, or sheer neglect or acquiescence, many of the most onerous decisions issued by Republican-majority labor boards have been allowed to ossify over the decades as “settled” law, despite often originating as reversals of long-standing precedent dating back to the earliest days of the NLRA.

The newly elected Biden administration can do something about this. While Joe Biden’s future appointments to the NLRB (however they obtain their seats) should focus on overturning as much of the Trump board’s anti-union decisions as possible, they should also examine decisions from the Eisenhower, Nixon, and Reagan boards, which were criticized in their own time for subverting the NLRA’s original intent of fostering industrial democracy in the American workplace. The fact that these rulings remain on the books today through historical accident or administrative inertia should not justify their continuous harmful effects on today’s workers.

While the Obama board was far too inactive in reversing older precedent, its King Soopers decision serves as a good example of why this is a project worth pursuing. The Democratic majority in that case reversed a seventy-four-year-old NLRB policy dating back to the Eisenhower administration (but even originating in the earliest practices of the Roosevelt board) which, in the context of employees discharged for anti-union purposes, were denied search-for-work and interim employment expenses that exceeded the discriminatee’s interim earnings, creating a loophole in which discriminatees unable to find interim employment were refused any compensation at all for their search-for-work expenses. This sort of administrative archaeology forced Trump’s general counsel to prioritize it for re-reversal and, eventually, have to justify why the Obama board was in error. As of this writing, King Soopers remains standing and receives favorable citations.

The following is a list of decisions or doctrines that the future Biden board should target for reversal. All ten reversals, if replaced by interpretations of labor law that often date back to the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, would strengthen the NLRA’s core principle of industrial democracy and increase workers’ bargaining power with their employers. While these decisions could be overturned by future Republican Boards, progressive appointees must resurrect these dormant issues and put the management-side lobby back on the defensive. Those who wish to weaken workers’ collective rights should be the ones playing whack-a-mole.

1

Liberate Workers from Forced Anti-Union Meetings.

The NLRB’s “captive audience” doctrine, which allows employers to compel their employees under threat of discharge to attend and listen to anti-union speeches on company time, has long been a thorn in the labor movement’s side due to its status as management’s most important weapon in an election campaign. Workers are subjected to captive audience meetings in nine out of ten union organizing drives, and drives see an average of ten such meetings.

No coincidence, then, that the doctrine has been targeted for legislative amendment in the most recent comprehensive attempts at labor law reform, the filibustered Carter-era bill in 1978 and the pending Protecting the Right to Organize Act. However, captive audience meetings can effectively be muzzled simply on a case-by-case basis.

Under the original Wagner Act from 1935 to 1947, captive audience meetings were considered unduly coercive and a “per se” unfair labor practice. The Truman board revisited this ruling after the insertion of the employer “free speech” provision as part of the Taft-Hartley amendments and held that while such meetings were no longer unlawful in and of themselves, they would still constitute an unfair labor practice if the employer held a mandatory meeting and did not afford the union an opportunity to respond with equal time on company property. The “equal time” rule lasted for only two years until the new Republican majority of the Eisenhower board held that employers were entitled to hold captive audience meetings without providing a platform for union organizers to respond.

This rule persists today. Unions would later lobby the Kennedy board to return to the “equal time” rule, but the Democratic appointees deferred until they could observe the results of their new Excelsior Underwear rule, which requires an employer to turn over a list containing the names and addresses of all eligible voters within seven days after an NLRB election has been ordered. This experiment has woefully failed to serve as a worthy substitute. As any organizer can attest, the union’s right to possibly get in contact with potential voters pales in comparison to the employer’s ability to force those voters to listen whenever it so desires.

The Biden board should level the playing field and return to the equal time rule constructed by the Truman board. Alternatively, the Biden board can go further and correct the Truman board’s original sin of allowing captive audience meetings at all. As law professor Paul Secunda has pointed out, there is ample wiggle room within the legislative history of Taft-Hartley to maintain a captive audience ban, as such bans should escape First Amendment scrutiny because they regulate employer conduct, not employer speech. Employers could only give their anti-union lectures to employees who actually want to listen to them.

2

Crack Down on Misrepresentations During Organizing Drives.

The NLRB has always taken a relatively hands-off approach to misrepresentations made by competing parties in the election context. As it has stated, “exaggeration, inaccuracies, half-truths, and name calling, though not condoned, will not be grounds for setting aside an election.” This is grounded in realistic expectations, for “absolute precision of statement and complete honesty are not always attainable in an election campaign, nor are they expected by employees.”

The importance lies in what the NLRB does with extreme cases. In 1962, the Kennedy board first articulated a workable standard against electoral sabotage:

[A]n election should be set aside only where there has been a misrepresentation or other campaign trickery, which involves a substantial departure from the truth, at a time which prevents the other party or parties from making an effective reply, so that the misrepresentation, whether deliberate or not, may reasonably be expected to have a significant impact on the election.

This standard gave an offending party several potential outs, but it was still too restrictive for Republican labor boards. In 1977, a mix of Nixon and Ford appointees held that the NLRB should get out of the business of regulating election propaganda altogether. Arguing that the Kennedy board’s standard was overly paternalistic, the new majority reasoned that union election rules “must be based on a view of employees as mature individuals who are capable of recognizing campaign propaganda for what it is and discounting it.” The NLRB would only overturn election results due to campaign misrepresentations that were made in the form of forgeries.

The Carter board reinstated the Kennedy board standard a year later, but the Reagan board subsequently reversed that reversal and adopted the deregulatory view. It is here that the carousel finally stopped. After years of relentless criticism by academics and practitioners regarding the Board’s seesawing approach, both the Clinton and Obama boards declined to revive the debate and have continued to turn a blind eye to virtually all campaign misrepresentations.

The agency is thus declining to do its job. Under its long-standing “laboratory conditions” doctrine, the NLRB is required to “provide a laboratory in which an experiment may be conducted, under conditions as nearly ideal as possible, to determine the uninhibited desires of the employees.” This regulation does not infantilize workers; rather, it recognizes that they often do not have the time or energy to parse every lie, trick, fraud, or forgery that comes their way in the course of an election — a disadvantage of which the employer is acutely aware. And the law’s banning of the latter tactic but acceptance of the former three makes little practical sense. Written deception can, in many instances, be more quickly verified than a whispering campaign.

While the Kennedy board standard opens the NLRB to criticism that it is eschewing a hard-and-fast rule in favor of case-by-case analysis, the parties that benefit most from predictability are employers and their lawyers. The NLRB’s first priority is not to cut down on litigation; it is to remedy unfair labor practices and assure free and fair elections. Holding parties responsible for their misrepresentations would best comport with the agency’s mission.

3

Prevent the Coercive Interrogation of Workers’ Union Sympathies.

The NLRB has, since its genesis, barred employers from coercively interrogating employees concerning their support for a union. The only thing that has changed has been what level of scrutiny is applied in determining what constitutes a “coercive” interrogation. While the Truman board initially held all forms of employer questioning regarding an employee’s level of union support to be unlawful, reasoning that “employers who engage in this practice are not motivated by idle curiosity, but rather by a desire to rid themselves of union adherents,” the Eisenhower board greatly relaxed this standard by creating a multi-pronged test (the Blue Flash rule) that purported to more accurately gauge the context of the questioning.

In one of its few major contributions, the Carter board briefly reinstated a per se unlawfulness standard for interrogations. Notably, this Democratic majority argued that even the questioning of open and known union adherents would likely coerce less solid supporters in the workplace, as any interrogation signals the employer’s clear displeasure with unions and its willingness to personalize the campaign. Reagan’s appointments quickly steamrolled over this nuance and reinstated the Blue Flash rule’s “all the circumstances” analysis.

This is the state of the law as it stands today. While courts expressed displeasure with the Truman and Carter boards’ rigid conception of per se violations, the failure of the Clinton and Obama boards to even strengthen the level of inquiry into employer interrogations represents an unfortunate surrender in this area. The Biden board should take note of the vast sea of academic research that demonstrates the dictatorial level of control employers wield over their employees and reverse this outdated aspect of labor law.

4

Deter the Commission of Unfair Labor Practices in Representation Elections.

“Card check,” by which a union is certified on the basis of a majority of signed authorization cards instead of through the NLRB’s election process, has long been one of labor’s most desired reforms (and, conversely, one of management’s most feared). It was the centerpiece of the failed Employee Free Choice Act and drew a frenzied response from management lobbies. The reason is that certification on the basis of authorization cards generally prevents companies from deploying the sort of anti-union campaign tactics described above to sap away a union’s majority before an election is held.

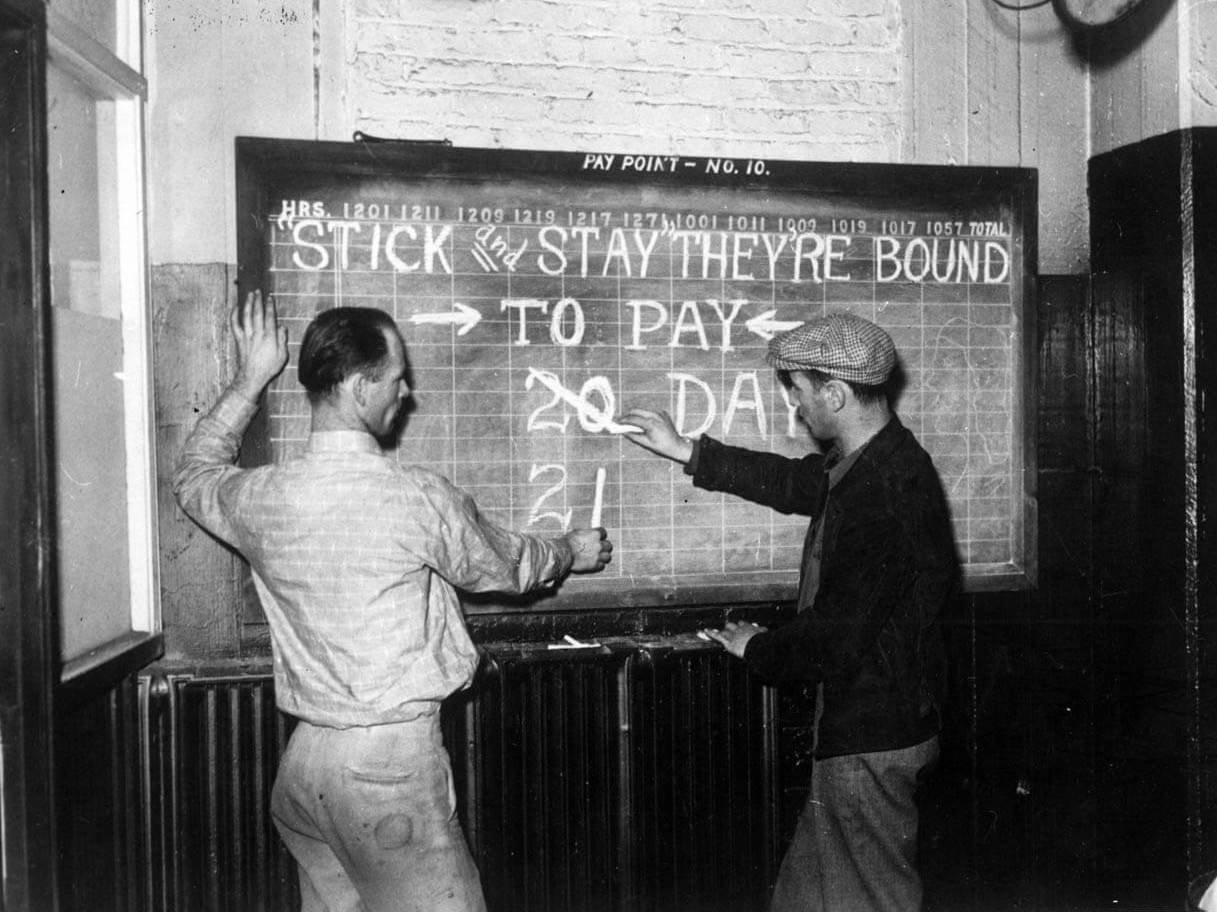

While card check failed in Congress, the Biden board can come close to achieving its goals by resuscitating a strand of case law that the NLRB adhered to for twenty years. Under the Truman board’s Joy Silk doctrine, the NLRB would order an employer to recognize and bargain with a union if it represented a majority of workers in an appropriate bargaining unit at the time it requested recognition and the employer denied the request while lacking a good faith doubt as to the union’s majority status.

Joy Silk made sense with the central tenets of labor law. The NLRA requires an employer to negotiate in good faith with a union designated by a majority of employees to serve as their bargaining representative. It naturally followed that when an employer was presented with signed authorization cards from a majority of the employees and did not have a reason to doubt the legitimacy of this majority support, the employer was unlawfully refusing to bargain.

If good reason existed to doubt the union’s claims, then the employer could insist that the union establish its majority through a representation election. But even if the employer provided valid grounds for doubting the union’s majority status, the NLRB would use the employer’s independent unfair labor practices to find a lack of good faith where such acts demonstrated “a desire to gain time and to take action to dissipate the union’s majority.”

Despite Joy Silk’s acceptance in every circuit court that reviewed it, management representatives regularly attacked the doctrine on several grounds: it placed the burden of proof on employers; it required the NLRB to subjectively interpret the employer’s intent based upon a few words of dialogue (or sometimes none at all); and it allowed unions to obtain a bargaining order despite the supposedly inherent unreliability of authorization cards. Of course, little effort was made to explain why a signature solicited by a union organizer was an obvious product of coercion, but an election held following an employer’s months-long blitzkrieg against the union equaled a true barometer of freedom of choice. (The historical record also reveals that the anti–Joy Silk movement received considerable help from liberal law professors, who shortsightedly lent legitimacy to the claims that the NLRB’s practices were onerous and conclusory.)

The “good faith doubt” analysis of Joy Silk was eventually abandoned for a more pro-employer approach that only sanctioned bargaining orders in the face of “outrageous” and “pervasive” unfair labor practices. The Nixon board further clarified that not only did employers not have to bargain with a union when presented signed cards from a majority of the proposed bargaining unit, but employers didn’t even have to ask the NLRB for an election; this, too, fell on the union to initiate. To this day, unions are forced to endure the negative onslaught of the election process except in the most extreme of circumstances.

As union lawyer Brian Petruska has convincingly demonstrated, the NLRB’s abandonment of Joy Silk opened the door for widespread employer interference in representation elections. Management has increasingly probed the outer boundaries of its free speech rights and found that the most common scenario in the post–Joy Silk world — an edict by the NLRB to rerun a tainted election — is well worth the opportunity to stall an organizing drive to death. The Biden board should return to a prouder time in its election jurisprudence and strive to put the “order” back in bargaining orders.

5

Reclaim the Meaning of “Concerted Activities.”

Consider two employees with identical safety concerns. One works in a union shop; the other is nonunion. The union worker files a grievance under his collective bargaining agreement; the nonunion worker files a claim with his state’s department of labor. At this point, the union worker’s employer may not lawfully discharge the worker for her decision to file. But the nonunion worker may be lawfully discharged for hers.

This is only so because of a cramped reading of the law by the Reagan board, which overturned an older decision that extended legal protections to individual employees who assert rights created for all employees by workplace-related statutes. Section 7 of the NLRA protects employees’ right to engage in “concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” In a case called Meyers, Republican appointees interpreted this language to mean that a lone act by a single worker — such as the filing of a wage or safety claim with a state agency — could not properly be construed as a “concerted” effort.

The problem with Meyers is that there is a Supreme Court opinion that expressly rejects this logic with regard to individual grievances under collective bargaining agreements. The Reagan board unconvincingly distinguished contractual rights from statutory rights by arguing that the former only exist because of the previous exertion of Section 7 (i.e., negotiating a labor agreement), while the latter is the product of legislative drafting too remotely related to the activities of employees in the workplace. But one federal circuit court rightfully skewered this cabined logic:

Statutory rights form the fabric upon which employees weave the pattern of their collective-bargaining agreement. . . . A labor-management agreement is not written on a tabula rasa; rather, it is created against the background of a panoply of statutory employment rights. Employees, conscious of the milieu in which they decide to organize and bargain, rely on the availability of the enacted rights they already possess.

The NLRA should not be read to exclude workers that invoke their rights in pursuit of better working conditions. Instead of imposing a standard that requires coworkers to explicitly signal their support of a worker’s complaint, it should be presumed that all employees care about something as universal as workplace safety. To hold otherwise creates a gulf between the Section 7 rights of union and nonunion workers, despite that provision being written to empower the unorganized masses.

In a divergence from the other cases highlighted in this article, general counsel Fred Feinstein litigated to overturn Meyers during the Clinton years. Inexplicably, neither of the two Democratic board members with union-side backgrounds agreed to reverse it, leaving chairman William Gould to pen a dumbfounded dissent in solo. “The acceptance or rejection of precedent on the theory of concerted activity indicates, perhaps more clearly than in any other area of the statute we administer, where a Board member stands on such critical matters as statutory construction and the scope of the Board’s role in administering the Act,” Gould would forcefully remind his colleagues. Biden’s appointees should take note.

6

Protect Solidarity on the Picket Line.

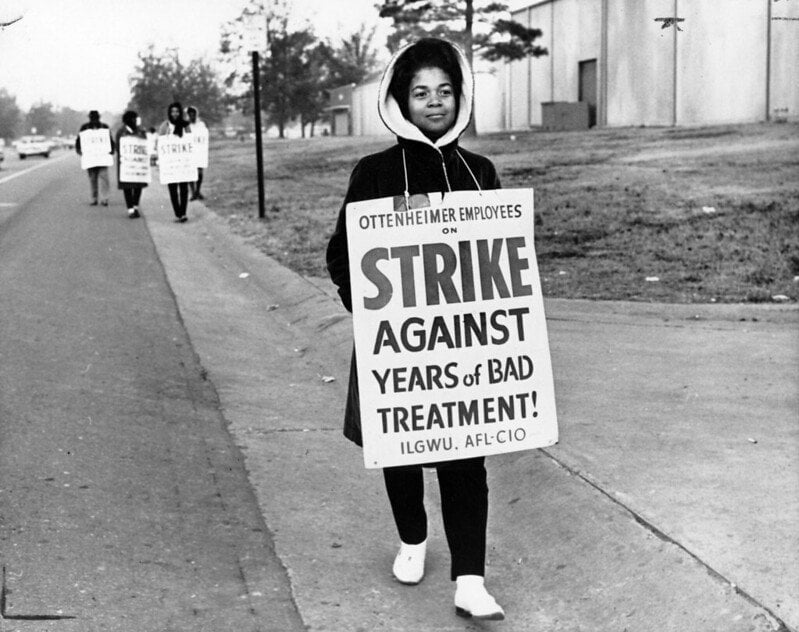

Labor law regulates both the conduct of parties at the bargaining table and what happens when talks break down. In the emotionally charged setting of picket lines, the NLRB had for decades refused to regulate the often-heated words exchanged between striking workers and their replacements. The NLRB acknowledged that because strikes produce strong emotion, strikers are not expected to observe “the rules of the parlor”; and some “exuberance” is to be expected (and tolerated) during a strike.

Under this rule, verbal threats, unaccompanied by any physical action or gestures, were not considered serious strike misconduct. And if unfair labor practice-strikers were discharged for potentially serious strike-related misconduct, the agency would balance the severity of the employer’s unfair labor practices that provoked the strike against the gravity of the striker’s misconduct. In many circumstances, the NLRB would find the employer the guiltier party and order reinstatement of the striker.

Not content with this level of adjudicative nuance, the Reagan board abandoned it altogether and replaced it with a per se rule against verbal threats of any kind. Any actions that “may reasonably tend to coerce or intimidate employees” would lose a ULP striker the protection of the NLRA and leave her open to discipline or even discharge. In that case, Clear Pine Mouldings, Reagan’s appointees elucidated an extremely neutered version of industrial relations that defanged labor in the exercise of its greatest weapon:

As we view the statute, the only activity the statute privileges in this context, other than peaceful patrolling, is the nonthreatening expression of opinion, verbally or through signs and pamphleteering.

The Reagan board did not bother to explain why it was tightening the screws on statements made by strikers at the same time it had moved to deregulate misrepresentations made during the course of organizing drives. But apparently spontaneous threats from one’s coworkers on the picket line are, in defiance of all basic power dynamics, more coercive than the meticulous and systematic threats from one’s provider of wages and employment.

Although later decisions have attempted to soften the Reagan board’s ruling, Clear Pine Mouldings remains on the books today as a lodestar for striker misconduct analysis. Indeed, this case was recently cited by the Trump board as inspiration for further crackdowns on “abusive” employee speech toward management.

The Biden board must uproot this unjustified intrusion into workplace conduct, which, as one legal commentator once noted, amounts to a “pious pronouncement that employees must deport themselves as ladies and gentlemen or risk the loss of the job that created the emotion in the first place.”

7

Restore a Semblance of Balance to Lockout Law.

While labor law is ostensibly rooted in the understanding that employers and their employees possess inherently unequal levels of bargaining power, NLRB case law is nonetheless riddled with false equivalences that ignore this guidepost. Perhaps most insidious among them is the legal fiction that the lockout is equivalent to the strike, despite the former’s absence from the NLRA’s main text and the latter’s explicit statutory protection.

For the first several decades of the NLRB’s existence, the agency prohibited employer lockouts except in “defensive” situations, i.e., in response to slowdowns, industrial sabotage, credible strike threats, or strikes designed to “whipsaw” all members of a multi-employer bargaining unit by targeting its weakest members with economic pressure.

The ban on “offensive” lockouts came to an end in 1965 when the Supreme Court held in American Ship Building Co. v. NLRB that employers may lock out employees solely as a means of imposing economic pressure on their union at the bargaining table. However, the court expressly left open the matter of whether employers could hire temporary replacements for employees that were laid off as the result of an offensive lockout.

This question fell to the NLRB’s policy-making discretion, and the Kennedy board quickly answered it in the negative. While these initial decisions hinged on the argument that employers could not justify such aggressive posturing on legitimate business reasons alone, the reviewing courts urged the agency to go even further and hold that employers could never employ temporary replacements because this was “inherently destructive” of the locked-out employees’ Section 7 rights to collectively bargain.

The Kennedy board never got the chance to implement this request before Nixon’s appointees walked back this case law into a sea of uncertainty. It was eventually resolved by the Reagan board’s incredible proclamation that an employer’s use of temporary replacements was reasonably adapted to achieving legitimate employer interests and had “only a comparatively slight adverse effect on protected employee rights.”

In other words, the NLRB treats a bazooka like a squirt gun. Even a cursory understanding of modern labor relations reveals that the offensive lockout, when deployed tactically by a cunning employer, essentially vitiates the right to strike. It inherently discriminates against employees that exercise their lawful right to collectively bargain by denying them work and offering it to nonunion workers. Whereas the union’s members are immediately forced to live off a fraction of their previous earnings while out of work, most employers will happily sacrifice a temporary dip in quality or output so long as production continues at all. It is thus hardly surprising that the use of offensive lockouts has skyrocketed in recent decades.

The current landscape is a policy choice. Although the NLRB was denied in its attempt to eradicate this economic weapon altogether, the Supreme Court gave the agency free rein to shape the ultimate effectiveness of these lockouts. Republican labor boards have endeavored to make them as devastatingly potent as possible in the hands of employers and have seen little to no resistance from the Clinton and Obama boards, despite their continuing proliferation.

The Biden board should recognize that the use of temporary replacements in opportunistically timed lockouts are inherently destructive of employees’ Section 7 rights and render their usage an automatic unfair labor practice.

8

Strengthen the Duty to Bargain Over Capital Allocation Decisions.

It may be hard to believe now, but the NLRB once banned management rights clauses and instructed employers to bargain over most capital allocation decisions — i.e., management determinations to close, relocate, reassign, or subcontract work. The Supreme Court has rebuffed the NLRB in these attempts and cordoned off most capital allocation decisions from bargaining due to their supposedly inherent nature at the “core of entrepreneurial control.”

This is an area of labor law begging for legislative reform, but NLRB members attentive to these issues can still do quite a bit of good through the agency’s adjudicative function. For example, the Carter board held that mid-contract decisions to transfer bargaining-unit work from a union shop to a nonunion plant constituted an unlawful refusal to bargain. Carter’s appointees reasoned that the transfer was an obvious ruse to avoid the collective bargaining agreement’s wage provisions and added that the contract did not contain any explicit language permitting the employer to transfer the work.

On remand of that decision a few years later, the Reagan board flipped this logic on its head: because the contract did not contain any language that did not permit the employer to transfer work, it was therefore an inherent management right that did not require bargaining. Apparently without shame, the Reagan appointees feebly reasoned that the wage provisions of the contract could not be violated because there were no bargaining-unit employees left for it to cover, and it was not the NLRB’s responsibility to “create an implied work-preservation clause in every American labor agreement based on wage and benefits or recognition provisions.”

One of the Carter holdovers pointed out in an indignant dissent that the majority’s decision permitted the employer to accomplish indirectly (by transferring the bargaining-unit work to an open shop) what it could not have done indirectly (unilaterally reducing the wages of the unionized employees).

Despite this clear evisceration of union bargaining rights and its broader meaning as to the employer’s duty to bargain, neither the Clinton nor Obama boards attempted to reinstate the Carter board’s interpretation. Instead, Democratic appointees have seemed content to let Republicans steer the ship. In the celebrated Dubuque Packing case, the H. W. Bush board softened the Reagan board’s stance on work relocation by enunciating a serpentine standard that defined what and would not be lawful:

Initially, the burden is on the general counsel to establish that the employer’s decision involved a relocation of unit work unaccompanied by a basic change in the nature of the employer’s operation. If the general counsel successfully carries his burden in this regard, he will have established prima facie that the employer’s relocation decision is a mandatory subject of bargaining. At this juncture, the employer may produce evidence rebutting the prima facie case by establishing that the work performed at the new location varies significantly from the work performed at the former plant, establishing that the work performed at the former plant is to be discontinued entirely and not moved to the new location, or establishing that the employer’s decision involves a change in the scope and direction of the enterprise. Alternatively, the employer may proffer a defense to show by a preponderance of the evidence: (1) that labor costs (direct and/or indirect) were not a factor in the decision, or (2) that even if labor costs were a factor in the decision, the union could not have offered labor cost concessions that could have changed the employer’s decision to relocate.

A normal person will read this passage and think, “Wow, that is very confusing.” A clever management lawyer will read it and realize that it supplies no less than six automatic outs from bargaining, and their client need only satisfy one of them. Nonetheless, this formula was soon praised in the leading treatise of labor law for “reducing uncertainty about the burdens of proof” and bringing “a measure of order to a body of law that is destined to remain unruly”: veiled language for sure union defeat in courtrooms.

As with the Meyers case, the lone enthusiast among Democratic board members for reversing these decisions was Chairman Gould. Gould wrote in a 1997 concurrence that the NLRB should jettison Dubuque Packing and simply require bargaining over work relocation in all situations “where the reasons underlying the relocation of unit work are amenable to bargaining and not solely to those decisions which implicate labor costs.”

This approach is far more faithful to the foundation of the NLRA, which states in its opening preamble that it was enacted to encourage the practice and procedure of collective bargaining. And if the duty to bargain is to mean anything, it must allow workers to have a say in whether their jobs will even continue to exist.

9

Fashion Adequate Remedies in Refusal-to-Bargain Cases.

There is perhaps no more flagrant violation of the NLRA than an employer’s refusal to bargain with a duly certified union — the industrial equivalent of plugging one’s ears and stomping one’s feet.

Unfortunately, this temper tantrum is often rewarded. Refusals to bargain allow the employer one last bite at the apple and initiate numerous institutional delays through the NLRB’s unfair labor practice proceedings, working to discourage employees’ enthusiasm for the union and their belief that collective action can produce material gains. Little surprise, then, that more than a third of unions that have won an NLRB election are unable to secure a first collective bargaining agreement within two years of certification.

The NLRB has a statutory mandate “to take such affirmative action . . . as will effectuate the policies” of the NLRA. This means the agency must calibrate its remedies to both cure the ills of individual cases and deter widespread wrongdoing. In 1967, the Kennedy board appeared ready to fashion a remedy that would require an employer to reimburse its employees for the loss of wages and fringe benefits that they would have obtained through collective bargaining if the employer had not unlawfully refused to bargain in good faith. The experimental case, Ex-Cell-O Corp., touched off a firestorm of academic debate and political lobbying as labor and management prepared for a world in which companies could not simply flout bargaining obligations at will.

But in an excruciating instance of administrative delay, the Democratic majority was not able to get out its decision before Richard Nixon won office in 1968. The moderates on the panel thereafter shelved the case until the new president got to weigh in on the controversy with appointments of his own.

Finally, in 1970, the Nixon board handed down its ruling in Ex-Cell-O: a sheepish capitulation that argued the agency was without power to order compensatory (“make-whole”) relief in refusal-to-bargain cases even in the face of an employer’s frivolous appeals. The majority reasoned that such relief amounted to compelling contractual agreement in contravention of the NLRA’s statutory “laissez faire” approach to bargaining; that the relief was too speculative; and that it would constitute an illegal punitive penalty.

In an unusual reversal of roles, the reviewing District of Columbia Circuit took a more expansive view of the NLRB’s powers and urged it to rethink its concession. First, compensatory relief wouldn’t be forcing contract terms on an employer; it and the union were free to bargain above or below the hypothetical wage and benefit amounts the NLRB would order as remuneration. Second, the mere fact that the relief would require speculation by the NLRB did not invalidate the approach, as speculative relief was a hallmark of much of American contract law. And third, while the Supreme Court has prevented the NLRB from ordering punitive damages, the relief in question was strictly compensatory rather than penal. Indeed, employers would otherwise receive a windfall from their intransigence.

The Nixon board refused the DC Circuit’s proposition and maintained in subsequent cases that the NLRB should not order make-whole relief in refusal-to-bargain cases. According to the majority, the mere fact that damages would largely be speculative — how could NLRB attorneys determine what a new union would have earned in wage and benefit increases if bargaining had taken place? — meant that they should refuse to contemplate this sort of remedy altogether.

But this belies a simple lack of motivation to redress employer abuses of the agency’s procedures. As contemporary commentators mentioned, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has tracked industrial economic data for decades. Expert civil servants could very feasibly base their calculations off these indices just as the National War Labor Board did in making its wage increase awards during World War II.

The Biden board should finish what the Kennedy board started and adopt the make-whole relief contemplated in Ex-Cell-O. Complaints that the relief is an “extraordinary” remedy should fall on deaf ears. Ex-Cell-O arguably represents the moderate position, as employees can never be fully compensated for an employer’s obstinance in negotiating a contract. How does one quantify the security, dignity, and other intangible benefits bestowed upon the workforce by a collective bargaining agreement? Industrial democracy cannot be boiled down to a number.

10

Recover the Enforcement of Public Rights From Private Actors.

Many actions by an employer may generate potential claims for a union under both the NLRA and its collective bargaining agreement. The most prominent examples are when the discipline or discharge of an employee may violate both the anti-union discrimination clause of the NLRA and the labor agreement’s “just cause” provision, and when a unilateral change in working conditions could violate both the NLRA’s duty to bargain and an express provision of the labor agreement prohibiting such changes.

Despite this framework appearing to give unions (and individual employees) multiple avenues of recourse, the NLRB will reflexively defer or even relinquish its jurisdiction to the grievance-arbitration machinery of a labor agreement. The Labor Board will defer to an arbitration award that presented potential unfair labor practice claims except under the most extreme circumstances (Spielberg deferral); it will defer to private arbitration when a grievance has already been initiated under that system (Dubo deferral); and it will even defer taking action on meritorious unfair labor practice charges when the facts giving rise to those charges may hypothetically be remedied through the parties’ system of private arbitration through a yet-to-be-filed grievance (Collyer deferral).

In effect, the public agency charged with preventing violations of federal labor law will subcontract a major portion of its statutory responsibility to a private system of conflict resolution with no comparable expertise in prosecuting those infractions. As you may have guessed by now, the NLRB did not always follow this path. The Roosevelt and Truman boards refused to recognize arbitration awards in general and independently examined the charged conduct for potential violations of the NLRA. They also held the agency open as a genuine option — rather than the secondary option — of resolution, finding that failure to utilize an available grievance procedure was not a bar to the processing of an unfair labor practice charge. The deferral policies only later crystallized under the Eisenhower, Nixon, and Reagan boards (with the exception of the concededly reasonable Dubo standard, which was initiated by the Kennedy board).

The single attempt to modify these standards in the last forty years came in 2014, when the Obama board narrowed the Spielberg standard for deferring to an arbitration award. That decision has since been reversed by the Trump board, but no actions have been taken to challenge the far more nefarious Collyer standard, which definitively subordinates the NLRB’s procedures to the private arbitral system. The Biden board should decline to follow this path and reclaim the agency’s status as the principal authority in remedying unfair labor practices by rejecting deferral policies altogether.

Admittedly, this final recommendation would likely be the most difficult to implement. Labor lawyers have practiced under the dominant religion of labor arbitration for over half a century, and the Republican supermajority on the Supreme Court appears content to let the Federal Arbitration Act swallow all of contract law whole. But the underlying assumptions of the NLRB’s deferral policies no longer apply. Collyer deferral in specific arose at a time when NLRB filings were exploding in number, leading to long delays in the handling of unfair labor practice charges, many of which could have been processed under the charging party’s contractual grievance system.

The NLRB’s caseload has since greatly diminished in volume. In addition, the leading luminaries in labor relations sincerely believed that arbitration would culminate in a sort of all-encompassing industrial jurisprudence for a widely unionized American workforce; unions would be accepted as a fact of life, and their complaints would be efficiently communicated and resolved through ever-evolving collective bargaining agreements. The outcome of that vision needs little elaboration. For the unionized companies that remain today, arbitration is simply a cheap and fast forum to flex a management rights clause or “split the baby” in a reinstatement case.

Democratic appointees should naturally be skeptical of any labor board policy that deregulates the agency’s enforcement mechanisms and places it in the hands of private actors. The Supreme Court has made clear in the past that the NLRB is not merely the runty little brother of labor arbitration that must leave the room whenever ordered. The NLRB should strive to become a trusted enforcer of the legal rights it was created to protect.

It goes without saying that the NLRB’s case-by-case adjudicative function is no substitute for genuine labor law reform in Congress. Any change recommended above could simply be reversed by the next Republican presidential administration that wins office.

But to just assume an administrative back-and-forth is to admit defeat and excuse neglect. Few would have predicted that Republicans would control the White House in twenty of the next twenty-four years following Richard Nixon’s win in 1968, and labor law was dramatically changed for the worse at a critical moment of mass deindustrialization.

While progressives cannot get back this lost time, they can assure that the next decade is not beholden to yesterday’s mistakes. Every decision or doctrine highlighted here was enacted by Republican labor boards and considered controversial in their time for creating a pro-management skew in the law. Of course, there are bad rulings handed down by Democratic majorities that are worthy of reversal as well: the worst aspects of the Mackay Radio case — which grants employers the right to hire permanent replacements during “economic” strikes — were greatly exacerbated by a Kennedy board decision. But the partisan dichotomy of the above-listed cases should send up a Bat-Signal of sorts to Democratic appointees. Why should anyone even mildly left of center accept the views of Reagan Revolution acolytes on issues as monumental as plant relocations?

Labor law can be as malleable as any other legal enclave. Its skeletal frame is mostly stuck in place, but the muscle and tissue within it can be grown and flexed. Biden’s NLRB appointees will have good reason to address its open wounds from the Trump board, but the agency’s older scars still need healing.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.