From Jacobin

In recent years, “anti-political” sentiment has taken root in Queensland, perhaps more so than in any other part of Australia. Its most obvious symptoms are declining support for the major parties and distrust of politics.

The long-term causes are structural: politics has been hollowed out as the membership of civil-society organizations — unions, church groups, etc. — steadily declined, depriving both Labor and the Liberal National Party (LNP) of their traditional social foundation. Meanwhile, wages have stagnated, and the fruits of successive mining booms have been squandered. As the links tying people to politics disintegrated, anti-political sentiment and alienation thrived, and the hard-right populists of One Nation reaped the rewards, increasing their vote while other parties declined.

The 2020 Queensland elections represent a dramatic reversal of these trends — although it’s too early to say whether this marks the beginning of a new one. Votes for both the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the LNP went up significantly — by 4.1 and 2.2 percent respectively — returning Annastacia Palaszczuk’s Labor government with an increased majority. One Nation was the big loser with its vote plummeting 6.6 percent. Mining magnate Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party only registered 0.6 percent of the vote.

The causes of this reversal aren’t hard to see. For the first time in years, government decisions had a tangible impact on people’s lives. Most people viewed Palaszczuk’s handling of COVID-19 positively, contrasting it with the much worse situation in Victoria, and thanking her for the low number of deaths and a low transmission rate, which meant that Queenslanders have been able to live something of a normal life during the pandemic. Those with a negative view of her government’s decisions seemingly shifted back to the LNP, believing that border closures meant a cost to small businesses and freedoms.

The Rent Is Too Damn High

There is still no evidence that the underlying causes of anti-political sentiment have been eliminated. While voters did reject right-wing populists, there was very little policy differentiation between the major parties on any issue other than COVID-19. Labor didn’t, for example, put forward a progressive economic-recovery agenda. So this election shouldn’t be read as indicating a broader shift to the left.

However, the Green vote was a notable exception. In contrast to One Nation, the Green vote essentially held up. The party’s state-wide 0.5 percent drop was primarily the result of a crowded field of candidates, as new parties entered the fray and existing small parties set their sights on new seats. Indeed, by holding their own, the Greens pulled ahead of One Nation to emerge as the third-largest party in Queensland.

The Greens also doubled their representation in Queensland’s unicameral state legislature, winning the prized seat of South Brisbane against Jackie Trad, former deputy premier and leading Labor Left figure. For the Greens, it was a modest but significant success, reflecting a number of trends likely to shape both state and federal politics for years to come.

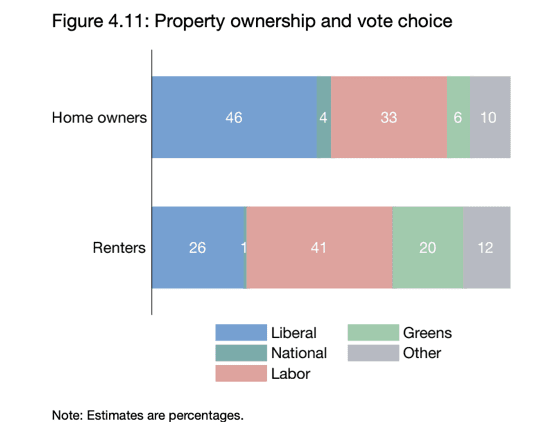

The rise of the renter is by far the most important determinant of a growing Green vote. The 2019 ANU Electoral Study found that the Greens polled at 20 percent among renters nationwide, compared to 6 percent among property owners. When measured against income and education differentials, the divide is much less stark. Among people with no post-school qualifications, the Greens poll at 11 percent, against 17 percent among those with university education.

Of course, “renters” are not a homogeneous group. But the term is a useful shorthand for an emerging social stratum defined by a lack of assets, stagnant wages, and precarious employment. These realities define the lives of an increasingly large layer of people, who, as a result, have no stake in neoliberalism. Even in a health crisis, economic insecurity makes a defense of the status quo unappealing to this social layer. To the contrary, they are open to a message that stresses fundamental social transformation.

By and large this economic layer skews young — largely because post-millennial generations have grown up in tandem with the slow-motion collapse of the neoliberal economic paradigm. The Greens have capitalized on this. In South Brisbane, for example, over 52 percent of residents are renters, compared with 30 percent statewide.

A Patient Strategy

Demographic realties, by themselves, only offer the possibility for building a left vote. To realize that potential takes sustained and strategic campaigning.

Where the Greens campaigned hardest, they bucked state-wide trends, achieving very large swings and winning votes from both Labor and the LNP. In the inner-west Brisbane seat of Maiwar, Greens MP Michael Berkman returned with a 14 percent swing. Incumbency was a factor, but only part of the story. The neighboring seat of Cooper saw an almost 10 percent swing to the Greens, putting what had previously been a safe Labor seat within striking distance.

Unlike left-wing electoral strategies in Europe and the United States, the Queensland Greens’ approach isn’t premised on a sudden populist surge. Instead, since 2016, the plan emphasized patiently and consistently building a movement capable of reaching people, primarily through face-to-face conversations.

This required an emphasis on political education for volunteers and members, focusing on clear communication. The goal was to convince people by relating policies to their material existence, and to connect this with opposition to the current economic and political system, working with a time frame of ten to fifteen years in mind to gradually build up Green political strength.

It paid off. In the inner-city seats of Cooper, Maiwar, South Brisbane, Greenslopes, and McConnel — areas where this strategy was deployed — the Greens saw substantial positive swings in their favor, and in the case of Maiwar and South Brisbane, historic wins.

These achievements were also made possible by the Queensland Greens’ boldest and most comprehensive platform to date. The platform’s lynchpin is a proposal to substantially increase mining royalties, to fund massive investment in health and education, to construct a hundred thousand public homes, and to shift the state to fully renewable energy by establishing a publicly-owned and -run manufacturing industry.

The basic premise was simple: rather than enriching a few billionaires, Queensland’s enormous mining wealth should be used to benefit every resident. Unsurprisingly, the message resonated deeply.

Talk to the People

Direct conversations with people at the door, on the street or over the phone were the secret to making this program devastatingly effective. By contrast, traditional campaign tools — print and online media and advertising — are largely ineffective. This is firstly because the Greens are easily outspent ten to one by their Labor and LNP rivals. Secondly, because declining trust in institutions includes a growing distrust in the media.

Nothing, however, beats one-on-one conversations. Volunteers and organizers recounted innumerable instances in which voters shifted to the Greens for the first time, after in-depth conversations that connected the party’s platform to their lives.

For example, an organizer for the Cooper campaign relayed a conversation with a young working-class mom who became emotional after hearing about the Greens’ plan to give every child a free season of club sport — she couldn’t afford for both her boys to play footy. Similarly, on election day, a volunteer for the South Brisbane campaign convinced a young couple to vote Green after a conversation about free hospital parking. The couple had a young boy undergoing chemotherapy, and the hospital parking fees had been devastating.

These conversations demonstrate, in microcosms, the power of building a coalition around a set of universally appealing policies and a shared material interest that’s opposed to mining billionaires, big banks, and property developers.

Although nothing beats one-on-one conversations, not all conversations are created equal. This is why political education is crucial. Rather than preaching about climate change and inequality, volunteers were trained to meet people where they are, and to talk to them about their issues. By offering a broader political and structural explanation for problems that directly affect people’s lives, this type of campaigning can have a lasting impact.

Green South Brisbane

Although the pandemic created disadvantageous conditions, the combination of politics and strategy meant the Greens were able to win South Brisbane. This had been a Labor heartland, held by the party since 1915. Before 2017, the Greens’ primary vote sat at 22 percent. Now, it sits at 38 percent — 3.5 percent higher than Labor’s primary vote.

To win South Brisbane it was necessary to make a convincing case against Jackie Trad and the Labor Left. For four years, this was a priority. In the end, sustained campaigning shifted the common sense that reinforces Labor’s vote, convincing residents that relying on the Labor Left is a failed strategy, and that Trad fundamentally didn’t represent them.

It wasn’t easy — winning the argument took over 9,500 in-depth, one-on-one conversations, spread over the six months leading up to the election. Volunteers knocked on doors, called voters, and chatted to people on the street.

The campaign also benefitted from the tireless community organizing work of Jonathan Sri, the Greens’ popular Brisbane City councilor. While Sri’s support for refugee rights might garner significant media attention, his work democratizing local politics is just as important. Brisbane City councilors are each given a $750,000 infrastructure fund. To allocate it, Sri established a participatory budgeting process. Now, the Gabba Ward, which elected him, has the most infrastructure spending out of any ward in the Brisbane City Council area.

In addition to this, Michael Berkman (Queensland’s first Greens MP, elected in 2017) and Jonathan Sri transformed their electoral offices into resources that can turbocharge and establish successful community campaigns. This was a further crucial component of the Queensland Greens’ strategy.

Victories create momentum. As the Queensland Greens elect more representatives, their capacity to build connections to civil society will expand exponentially, laying further foundations for a resilient movement capable of wielding real power.

Indeed, Michael Berkman was able to lead the rollout of one of the most progressive platforms Queensland has seen, while at the same time weathering a coordinated attack campaign by the mining lobby and Christian right. In fact, Berkman increased his vote share by 14 percent in a previously conservative seat — the outcome is in part a testament to this resilience.

But if there’s one lesson to take from this election it’s that to build a left vote, committed and politically educated organizers and volunteers are indispensable. Thanks to their determination, the Queensland Greens emerged with double the representation — and this will lay the basis for future victories.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.